“Da Vinci never finished his paintings. He got bored by the time he got to the corners.”

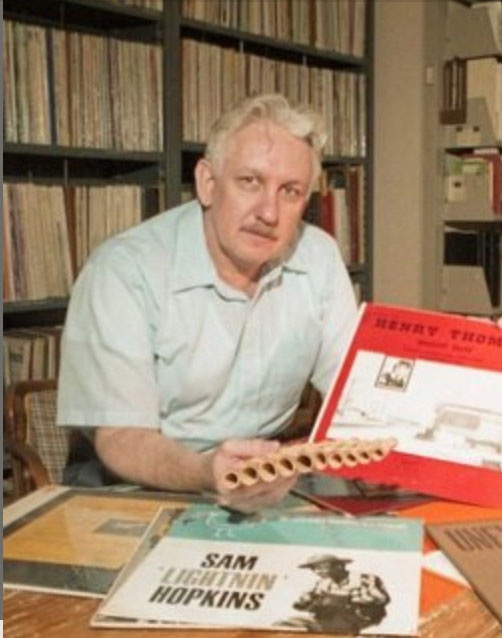

So said Robert Burton “Mack” McCormick, one of the most famous people to have called Spring Branch home. Famous, that is, if you are serious about the history of American popular music, more specifically the blues. In that world of music scholarship, McCormick’s name and achievements were known from New York to London, Tokyo to California.

So said Robert Burton “Mack” McCormick, one of the most famous people to have called Spring Branch home. Famous, that is, if you are serious about the history of American popular music, more specifically the blues. In that world of music scholarship, McCormick’s name and achievements were known from New York to London, Tokyo to California.

Enigmatic, secretive, and mercurial: McCormick — who suffered from bipolar disorder, was given to abandon massive book projects he’d begun with gusto, and to suddenly end friendships and/or working relationships for transgressions slight or imagined — accomplished a thousand small things that enabled others to do big things.

For example, McCormick’s renown partially rests on the hand he had in reinvigorating the career of Lightnin’ Hopkins, Houston’s most famous bluesman, and also the first recordings of Mance Lipscomb, a Navasota sharecropper whose repertoire included blues, ragtime, country, and Tin Pan Alley pop standards like “Long Way to Tipperary” and “Shine On You Harvest Moon.”

Lipscomb was 65 and almost completely unknown beyond Grimes County when McCormick helped him get in a recording studio. Within a few years, Lipscomb was a fixture on the national folk-blues festival circuit, appearing alongside Bob Dylan and Muddy Waters. Today, there’s a statue of Lipscomb in downtown Navasota that would not be there were it not for Mack McCormick.

So rich was the bounty of Houston and Texas talent McCormick had unearthed, it inspired a young German immigrant named Chris Strachwitz to found Arhoolie Records, a now 60-year-old imprint whose expansive catalog includes conjunto, New Orleans jazz, Appalachian old-time and bluegrass, vintage R&B/early rock and roll, traditional European music, country and western, Cajun music, regional Mexican, and zydeco. In 1986, accordionist Flaco Jimenez’s Arhoolie record Ay te Dejo en San Antonio won a Grammy. And the Smithsonian Institution has taken all of Strachwitz’s recordings under its wing.

Again, not possible without McCormick, whom Strachwitz met in 1959 through Sam Charters, another blues scholar. Charters sent Strachwitz a postcard telling him that he’d tracked down Hopkins in Houston (Strachwitz was a fan of Hopkins’s late-’40s-early ‘50s hits) via McCormick, who was then attempting to manage Lightnin’s flickering career. Had that not happened, Strachwitz remembered earlier this year, “I would probably never have taken a bus to Houston that summer nor gotten to know all of Texas the way I did. And I probably never would have met Mance Lipscomb, Lightning Hopkins, Clifton Chenier, the zydeco world, the Cajun and Creole world, etc. You can call it lady luck, fate, or my guardian angel — whatever you wish — [but] it changed my life and I would never trade it for anything!”

McCormick was born in 1930 in Pittsburgh, the son of X-Ray technicians who divorced shortly after his birth. McCormick ping-ponged between their homes, which changed often: Before he reached adulthood, he’d lived in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Colorado, West Virginia, Alabama, and Houston, where he settled for good beginning in the late ‘40s. (He moved to his little house on Autauga Street, across from Binglewood Park, sometime in the 1970s.)

A high school dropout whose mind devoured books on every subject, McCormick worked a variety of jobs as a young man, ranging from carnie to barge electrician to Texas correspondent for Down Beat magazine, then a widely-read publication dedicated to jazz. McCormick eventually got a job as a cabbie and that opened his eyes to the music all around him in Houston’s less well-traveled (to whites, anyway) neighborhoods.

And then he followed up that avocation with a stint as a census worker, pounding the pavements of Fourth Ward, which was a hotbed of Black music, especially by piano players. McCormick found some 200 of them there, all of whom, he believed, formed a unique “school” of performance derived from one man, long ago: a New Orleans native who went by Peg Leg Will and performed in front of Passante’s Grocery in Fourth Ward. A few learned directly from him, and then went on to teach others.

Rival Italian Fourth Ward grocers, jealous of Passante’s success, brought in pianos, and those pianos created more players, and before you knew it, McCormick believed, there was a Fourth Ward style of bluesy piano that was unique to the neighborhood that created it.

The jobs as cabbie and census worker were what made him so invaluable an asset to Strachwitz. McCormick taped and took notes on all these encounters, and the many to come, and compiled them into a huge home archive whose sheer scope and size came to intimidate McCormick. After a precious few examples of sharing his work with the world — as in the extensive liner notes to an album by Henry “Ragtime Texas” Thomas, whose name you might not know but whose work you just might. His “Bull Doze Blues” was adapted and re-released by the California blues-rock group Canned Heat as “Going Up the Country” and is now classic rock fodder and the centerpiece of major ad campaigns. Thomas, a railroad hobo born in 1875, played not just the earliest blues but also styles of music even older. He accompanied himself with quills, panpipes fashioned out canes cut from the bottomlands. McCormick’s liner notes on Thomas’s one and only record are some of the ablest scholarship into the pre-blues, pre-recorded era of African American music available to this day.

But after that … McCormick’s projects got the best of him. He spent months if not years chasing the ghost of Robert Johnson in Arkansas and Mississippi and claimed to have scored two photographs of the spectral bluesman from Johnson’s half-sisters long before any of his verified likenesses came to light. These he intended to publish in a book about Johnson to be entitled Biography of a Phantom. But he never completed the book, nor a history of the Texas blues he embarked upon with British researcher Paul Oliver. (Dallas folklorist Alan Govenar has since compiled an unfinished version of the book for release.)

Da Vinci, not painting the corners….it seemed like he let all the knowledge he’d assembled pile up to the point where writing about even a little of it was impossible, as each one of the strands he’d collected led to another, and another, and another, and he was incapable of telling any of it if he couldn’t tell it all. He came to call his archive “the Monster.”

He had some odd footnotes to his career. It was he who codified the spelling of zydeco. Prior to his efforts, the style, which derives its name from the Creole pronunciation of the French les haricots (“the beans”), was billed as “zordico,” “zologo,” “zodico,” and so on. McCormick fiddled around a bit with a sheet of paper and a pen and inserted the “y” (because he thought it gave the word a sci-fi edge) and put it out on posters and albums by Clifton Chenier and now that’s just the way it’s spelled.

A failed playwright, McCormick was also a respected lay scholar on Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson.

He could also possibly be the source of the possibly untrue story that folk singer Pete Seeger attempted to silence Bob Dylan’s pivotal electric music Newport Folk Festival performance by hacking through the band’s electrical cords with his trusty ax. According to McCormick, it didn’t happen that way at all — he said he pulled the plug on Dylan because he needed the stage for his group of singing Texas ex-cons to practice, and Dylan’s band rehearsal was so loud he couldn’t hear McCormick telling him his time was up.

And there was a controversy near the end of his life when a hired researcher and shared a sliver of information from the Monster with the New York Times’s John Jeremiah Sullivan. It was only a shred of information, but of great import to blues fans and scholars and Houstonians: It documented the hitherto-unknown origins of the utterly haunting, astoundingly brilliant country blues tune. “Last Kind Word Blues.” All that was known of the song was that it was performed in Grafton, Wisconsin for the Paramount Label by two women — Geeshie Wiley and Elvie Thomas, who also recorded a few more tunes for them, and then vanished from history.

There is a tendency to ascribe all the best blues to Mississippi and that is what happened to “Last Kind Words Blues.” In the absence of any story to the contrary, it was assumed to have come from Mississippi and was billed as such via its inclusion on compilation albums for Mississippi greats. During that time its fame spread far and wide. It has a star turn in “Crumb,” the award-winning documentary about the old-timey music-loving cartoonist and illustrator R. Crumb. Critics have called the song “simply one of the best performances in early country blues” and said of Wiley that she “may well have been the rural South’s greatest female blues singer and musician.”

Well, maybe not so rural, because the information McCormick’s researcher spirited to the New York Times revealed that Wiley and Thomas were actually not from Mississippi or anywhere rural but instead Houston’s Fourth Ward.

And so the music world was left wondering what else the Monster held. And it still does, as the fate of “the Monster” has been a secret since McCormick passed away five years ago. We’ve asked around, and heard from a reliable source that its next home will be an institution worthy of its contents. Watch this space for further developments as they become available.

By John Nova Lomax